All Intervening Steps are of Interest: A Discussion of Christo’s Drawing’s

“If the artist carries through his idea and makes it into visible form, then all the steps in the process are of importance...All intervening steps are of interest. Those that show the thought process of the artist are sometimes more interesting than the final product” Sol LeWitt

When I set about to write this essay, I had a very clear intention to explore the question of whether or not Christo’s drawings have been critically discussed separate from his environmental interventions. Shortly into my research however, it became blatantly aware that in fact, no, no one analyzes the drawings. Each time a drawing of his is mentioned in an essay, article or book, it is quickly dismissed simply as a preparatory exercise and a device implemented to fund his and Jeanne Claude’s ambitious projects. No one regards the drawings as a practice in their own right. The closest we get is a short paragraph in a review by Jay Gorney in 1976 in which he makes mention of Christo’s ability as a draughtsman and colorist, but says nothing more. No critical analysis of the drawings, no examples specifically of how Christo is a good draughtsman or colorist, just a brief quip that he indeed demonstrates that ability in his drawings. Even Christo and his wife Jeanne-Claude - who wass his art and business partner - are guilty of passing the drawings off as preemptive plans and a fund raising tool. In an interview with Sculpture Magazine, Jeanne-Claude states very precisely that “all the drawings are called preparatory drawings because they are created exclusively before the completion of the project, never afterward.” For them to pass them off as nothing more demonstrates the common assumption that they don’t possess any more uses, and perhaps it is because of Christo’s own assignment of the drawings’ purposes that the art world has come to this unanimous agreement. Barnett Newman had a similar experience with his own work. In an interview with Dorothy Gees Seckler, he explains in that interview that drawing is what advances artists’ ability to see, and that innovation in the art world comes from that medium. He states in that interview “I prefer to talk on the practical or technical level...I mean the drawing that exists in my painting. Yet no writer on art has ever confronted that issue.” So it is the same here. The art world doesn’t want to focus on the drawings by Christo, even though they could open up and progress the way we view the rest of his practice, as well as the art world as a whole.

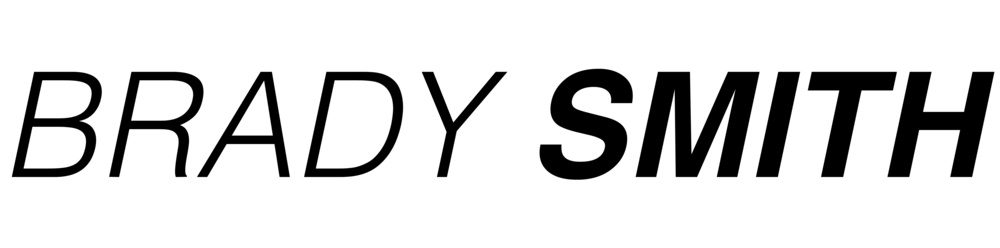

It would appear however that because no one cogitates the drawings, that they are not valued in the art world; that because they are quickly passed off as nothing more than a doodle that raises money, that there is no appreciation for them. This notion is gravely flawed however. For starters, the mere fact that couple chose to include the drawings on their website after stating multiple times that the drawings have no purpose once the work is actualized evidences that they, themselves, find more use for them post actualized interventions. And once again, looking at the couples’ website, you will find a timeline which shows how long the preparatory stages took in comparison to the physical life of the projects. (fig. 1) They want you to see how long the precursory works took. They want to instill in the visitors of the website an appreciation of the time, energy and effort put into getting these environmental works realized. If they truly felt that the work alone is in the finalized sculptures, then there would be no reason to point out all of the preconceived labors, which include these drawings. It is also interesting to see how well the drawings do in their later course of existence in secondary sales. In 2012 alone, Christo brought in $5,197,665 USD at auction. Because this figure comes from auctions, it proves that the drawings are indeed producing monetary value after the funding period has ended. These works are being resold on the secondary market years after the projects which they are presenting have been actualize. To say that the drawings’ purposes end when the work is created is to say that over 5 million dollars is being spent to buy drawings that aren’t art and no longer have a reason.

But more interesting than any of the aforementioned evidences of perceived value of the drawings is the reality that Christo has produced drawings for works that neither need a funding or any sort of preparation. In the beginning of his practice, Christo made drawings of wrapped cars, couches, telephones, unrooted trees and many other objects which he also physically wrapped. These drawings had aesthetic purposes separate from the physical wrapping of the objects. By saying Christo’s drawings are created in order to fund bigger projects negates the fact that the early wrapped objects don’t require funding of any sort. Wrapping a chair in his studio by no means takes an exorbitant amount of money, nor does it take much preparatory thought. If you want to know what a wrapped chair looks like, you just wrap it. (fig. 2 &3) Looking at his collaged lithographs of wrapped telephones raises an even more curious situation though. Christo’s ‘Wrapped Telephone’ was made in 1962, however the edition of two-dimensional work for the phone wasn’t made until 1988, 26 years after the physical work was realized. These pieces weren’t created as an exercise for wrapping the object because it was already wrapped. They weren’t sold in order to raise money for the project, because it had been completed for a over quarter of a century. This edition was produced then, as a work of art on its own, separate from the 1962 ‘Wrapped Telephone,’ thus Christo’s drawings can and must be examined separate from the works they are allegedly preparing for.

What frame works exist in which to situate these drawings that so far have no ground to stand on their own? What pedagogic discourses correlate with this vast body of works produced? And most importantly, what happens to the drawings when looked at through the scope of various ideas and practices modeled by other artists? Christo’s drawings explore many facets of the two-dimensional mark making language. He combines drawing with photography, lithography, text, collage and assemblage to accurately display the project the best he can before it is made. When combining these different mediums together something peculiar occurs. By playing with the preconceived notions of what each of these mediums can express, one’s sensations are altered, forcing the viewer to reexamine what is reality and what is imaginary.

For organizational purposes, I will divide and examine four areas of Christo’s two-dimensional practice in order to present possible applications for discussion of this large portion of his practice: drawing, text and documentation, photography and lithography, and collage and assemblage.

I

Drawing

Through the simple act of drawing, Christo discusses three key elements: role of artist as author, site specificity, and humans interaction with landscape

Christo’s act of drawing is essential to look at in relation to his control over the work. By making marks on the images, he reminds the viewers that he, as the artist, is in charge. Barthes writes in ‘Death of the Author’ “Once the author is removed, the claim to decipher a text becomes quite futile. To give a text an author is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing.” In the case of these drawings, the artists hand in the work is the only way for Christo to impose a limit on what is to happen to the work. The quick marks signifies that there is a human working the image, that an artist has put his hand to paper in order to create what you are looking at. This is imperative to Christo that if he is to remain the author of his work (which ultimately he wants to. The purpose of funding on his own, is to avoid other people being in charge of his projects). Once the works are realized, they are manufactured and assembled by a team of people. There is no signature on the fabric, and aside from the fact that traditionally Christo wraps/surrounds things in fabric, there is no evidence on the work that it is by him. The drawings stand in place of that signature, the drawings hold intact his authorship.

The drawings also act as a platform to imagine the works. In this instance the paper could be looked at as the initial site for the work. Historically, the topic of site-specificity is very much related to Christo because of his close association with land artist (which he has divorced himself from time and time again) as well as other environmental artists. The key difference between his practice and those of the artists in his time however, is that their preparation was far less materialized and completed. When looking at preparatory drawings by Robert Smithson for projects like his ‘Spiral Jetty’ it is very obvious that in fact, the work would not exist until the jetty was actually made. (fig 4) His quick spiral sketches are nothing more than a brief exploration of what the work could become, but it in no way allows the viewer to perfectly imagine what the sculpture may be. Christo on the other hand, completes his drawings and makes aware what the experience of seeing the work will be like. He creates a prequel to the interventions that so clearly and indubitably examine how the project will look, that the drawing itself, in a sense, becomes its own site as it were.

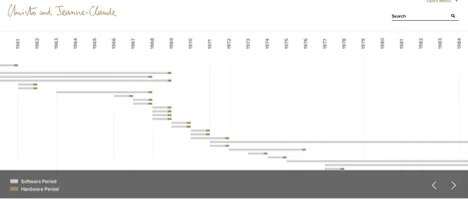

His ability as a draughtsman in an integral part of the success of the drawings. His understanding of how to make an interesting line so the drawings don’t become boring and banal is unmatched. In the drawings for ‘Running Fence (Project for Marin and Sonoma Counties, State of California)’ Christo plays with a quick gestural mark indicating where the fence will be placed. (fig. 5) This gestural mark making harkens back to action painters of the 50’s and their quick strokes of color on a canvas. Painters like Fanz Kline or Brice Marden explored the ways in which gestures can indicate an action or movement. By Christo creating these lines in reference to land, it makes the viewer imagine these physical marks scarred onto the landscape. Imagining a giant white line left on the surface of the earth as one quick active line, as though the gods were drawing and marking the landscape creates a subliminal experience. In the book On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century the purpose and ability of a line is discussed in depth. “In the twentieth century, many artists made line the subject of intense exploration, including semiotic and phenomenological investigations. By line as such, they understood its pure existence in the world and the meaning that could be attributed to this existence as creative intention and interpretation.” In the drawings for The Gates, he uses gestural, organic lines again, imitating human’s hand on the land, which raises a juxtapositions of nature vs man. The Gates was made up ofseries of arches with orange fabric draped from one to the other through New York Cities’ Central Park. The drawings show the gestural mark made by the artist, indicating humans interjection on nature, however, he is making this mark on a man made park raising the question of what is nature? Is his organic mark more natural and more at ease than the forced setting of nature in a large metropolis like New York City?

II

Collage and Assemblage

The genesis of collage and assemblage is very much in the modernist tradition, starting with the cubists collages of Picasso, Braque and Gris, then moving into more chaotic, but still tidy collages by the Dadaists like Hannah Hoch. As time continued one, more raw and intrusive materials were being added, altering the scale and perception of what were traditionally smaller works. What once would have been a small, intimate collage by Kurt Schwitters is progressed in the 60’s to large canvases covered in a hodgepodge of materials including (but not limited to) tires, quilts, mattresses, and taxidermy eagles (thank you Rauschenberg). Christo takes the materiality and scale of the latter, self-titled ‘neo-dadaists’ and perfectly marries it together with the precise and careful approach of earlier artists like Schwitters to create not only a style that is uniquely his own, but also creates a very interested experience.

The scale of the picture plane in Christo’s drawings is completely thrown by collaging a photograph or tightly rendered lithograph, obstructs it with a piece of real fabric and string. The scaled down photograph or lithograph combined with the not scaled down fabric makes the image seem as thought the fabric were gigantic and something not of this world. In 1971 Christo made an edition of lithographs for a proposal to wrap the Whitney Museum. (fig. 6) This edition of 100 were all individually altered with collage, drawing and writing. He attached fabric to the lithograph to indicate how the fabric may look when the work would be realized (which it never was). The texture of the fabric is extremely coarse and the twine that is stapled to the drawing also has a very raw materiality. When placed against the tightly drafted lithograph below, it makes it appear as thought the texture of the fabric on the actualized work would be incredibly large. The proportions of the building to the fabric are modified greatly. Much like the attempts made by the surrealists to question our conscious vs our subconscious, Christo here explores the human mind and its ability to produce and deviate from what is understood as reality. Where Magritte asks the question of whether or not you are looking at a pipe, or a painting of a pipe, you as the viewer of Christo’s work must ask yourself what the experience of being faced with fabric blown out of proportion covering a large building or surrounding an island would be like. The ability of the mind to imagine this creates a new space for the work to exist and causes a sensation exclusively owned by the two-dimensional works.

III

Photography and Lithography

It is very interesting that Christo incorporates tightly rendered, mechanical mediums such as photography and lithography with his loose, gestural drawing. What happens is a provocation of proportions and perspective. By working on top of precisely executed photographs and lithographs Christo once again plays with sensation and what is reality. The reality of the collaged material and very apparent presence of the artist in the lines drawn flattens and disorientates the truest representation of reality on the work: the photograph and/or lithograph. In the same way Picasso calls to question mechanical reproduction in his ‘Still Life with Chair Canning’ (fig. 7) by combining machine made texture with natural painting, making the viewer wonder which is the real thing, and essentially flattening the real texture caused by paint, the photographs in the works by Christo are flattened and pushed into the distance, making them more abstract and gestural than the loose, messy lines atop them. In an essay on what he calls ‘The Flatbed Picture Plane‘ Leo Steinberg explains that shifts in art making in the post war era caused paintings to appear horizontally, rather than vertically, literally flattening their presence. He writes “What I have in mind is the psychic address of the image, its special mode of imaginative confrontation, and I tend to regard the tilt of the picture plane from vertical to horizontal as expressive of the most radical shift in the subject matter of art, the shift from nature to culture.” This shift from nature to culture can appropriated here to explore the specifics of Christo’s general practice. Because of the photography and lithography used to flatten the picture plane and cause this shift, his drawings can be not only a literal representation of what is to come, but also a symbolic metaphor for the projects when they are actualized. He chooses to be associated with environmental artists because he chooses social sites to intervene. By making interventions in these cultural and social sites, he gives the opportunity to question what you are actually experiencing and whether or not it is nature.

Steinberg later goes on to say that “the picture conceived as the image of an image. It’s a conception which guarantees that the presentation will not be directly that of a worldspace, and that it will nevertheless admit any experience as the matter of representation. And it readmits the artist in the fullness of his human interests, as well as the artist technician.” It is this presentation of an altered reality that makes the drawings so crucial.

IV

Text and Documentation

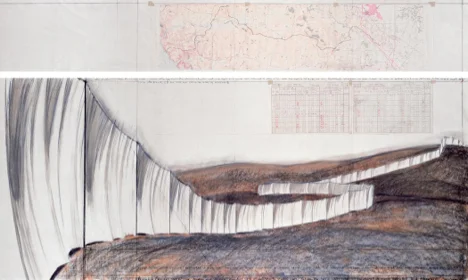

When talking about their work, the couple once said “We’re probably the only artists that make people think before a work exists.” And how do they make people think before the existence of a work? Their drawings. Christo and Jeanne-Claude time and time again, deny the label of being called conceptual artists because they see the works through till the end rather than leaving the works undone and as simply an idea alone. This deliberate division from the entire discourse of Conceptual art is doing a great disservice for the couples practice as whole. The notion of documentation as art allows for a whole new field of explanation and exploration in their work. When comparing Christo’s drawings to those of artists like Douglas Huebler, an entire movement unfolds within the projects. Not only are the aesthetic qualities obvious with their use of maps, text, photographs and artist made markings, the process to get there are also very similar. Conceptual artists’ process began with an idea, and often a set of instructions would then be established in order to see the idea through. In works like Huebler’s ‘Site Sculpture Project, Windham College Pentagon, Putney, Vermont’ (fig. 8) or Dennis Oppenheim’s ‘Directed Harvest’ the artist takes on the role of instigator and director. They construct a set of rules and directions in which the work is to be carried out, and then after, and only after, the result is presented, but the rules and ideas are still made before the actual event takes place. One could argue that the directions manifest by the artists are in fact where the work likes. In this case, Christo’s drawings would be looked at as the work, and the physical environmental intervention made my his team is only the result of the drawing and stands only as evidence that the drawing was made. You have a prequel/sequel situation presented.

Of Grammatology by French philosopher Jacques Derrida, explains that text is the driving force in contemporary society, and that nothing can escape it. ‘Il n’y a pas de hors-texte‘ or ‘there is nothing outside of the text‘ is the primary argument in the book. He explains that “If art lives from an originary reproduction, the outline that permits this reproduction, opens in the same stroke the space of calculation, or grammaticality, or rational science of intervals and of those ‘rules of imitation’ that are fatal to energy.” When examined through this context, the drawings are opened to the ‘same stroke of space or calculation’ as the work they precede. The drawings become the text on which the entire work is predicated. Nothing is outside the text, meaning, nothing is outside the drawings. In the end, the drawings are where the work lies, and is what should truly be discussed in regards to Christo’s practice.

Work Cited

Ackerman, James. "On Judging Art without Absolutes." Critical Inquiry, Spring 1979.JSTOR.org (accessed May 6, 2013).

Barthes, Roland. "Death of the Author." tbook.constantvzw.org. www.tbook.constantvzw.org/wp-content/death_authorbarthes.pdf (accessed May 6, 2013).

Buchloh, Benjamin, Rosalind Krauss, Alexander Alberro, Thierry de Duve, Martha Buskirk, and Yve-Alain Bois. "Conceptual Art and the Reception of Duchamp." October, Fall 1994. JSTOR.org (accessed May 6, 2013).

Butler, Cornelia H., M. Catherine de. Zegher, and N.Y. York. On line: drawing through the twentieth century. New York: Museum of Modern Art ;, 2010.

Castro, Jan. "A Matter of Passion: A Conversation with Christo and Jeanne-Claude."International Sculpture Center - Publisher of Sculpture Magazine. http://www.sculpture.org/documents/scmag04/april04/WebSpecials/christo.shtml (accessed May 6, 2013).

Derrida, Jacques. ‘The Engraving and the Ambiguities of Formalism’, in Art in Theory1900-2000 (Massachusetts, 2003, Blackwell Publishing) New Edition, p. 948

Dimendberg, Edward. "These Are Not Exercises in Style." October, Spring 2005. JSTOR.org (accessed May 6, 2013).

Downs, Simon. Drawing now between the lines of contemporary art. London: I.B. Tauris, 2007.

Fie, Wan, and Thierry Ehrmann. "Top 500 Artists by Auction Revenue in 2012." InThe Art Market in 2012. Paris: artprice.com, 2013. 78.

Finch, Charlie. "Him and Her." artnet.com. http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/finch/christo-and-jeanne-claude5-10-10.asp (accessed May 6, 2013).

Findlay, Robert, and Ellen Walterscheid. "Christo's Umbrellas: Visual Art/Performance/Ritual/Real Life on a Grand Scale." TDR, Spring 1993. JSTOR.org (accessed May 6, 2013).

Gabrillo, James. "An Abu Dhabi audience with exterior decorator Christo." Christo J-C (blog), November 16, 2011. http://christojeanneclaude.net/mobile/posts?p=an-abu-dhabi-audience-with-exterior-decorator-christo

Gorney, Jay. "Drawing Today in New York."Art Journal, Winter 1976. JSTOR.org (accessed May 6, 2013).

Harper, Paula. "Financing "The Gates"." Art in America, September 2005.

Kelley, Mike. "Shall We Kill Daddy?." Striking Distance Intro. http://www.strikingdistance.com/c3inov/kelley.html (accessed May 6, 2013).

Kosuth, Joseph, and Seth Siegelaub. "Joseph Kosuth and Seth Siegelaub Reply to Benjamin Buchloh on Conceptual Art."October, Summer 1991. JSTOR.org (accessed May 6, 2013).

Lemisch, Jesse. "Art for the People? Christo and Jeanne-Claude's "The Gates" | New Politics."New Politics. http://newpol.org/content/art-people-christo-and-jeanne-claudes-gates (accessed May 6, 2013).

LeWitt, Sol. ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’, in Art in Theory 1900-2000 (Massachusetts, 2003, Blackwell Publishing) New Edition, p. 848

Newman, Barnett. ‘Interview with Dorothy Gees Seckler’, in Art in Theory1900-2000 (Massachusetts, 2003, Blackwell Publishing) New Edition, p. 784

Seaton, Richard. "Art and Value Alternatvies." Leonardo, Fall 1978. JSTOR.org (accessed May 6, 2013).

Shepherd, E.. "Christo Running Fence." Oberlin College & Conservatory. http:// www.oberlin.edu/amam/Christo_RunningFence.htm (accessed May 6, 2013).

Steinberg, Leo. ‘The Flatbed Picture Plane’, in Art in Theory 1900-2000 (Massachusetts, 2003, Blackwell Publishing) New Edition, p. 972

Tenev, Georgi. "CHRISTO AND ALL THOSE BAD THINGS." Vagabond, Bulgaria's first and only monthly magazine in English. http://www.vagabond-bg.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=600&Itemid=26&limitstart=1 (accessed May 6, 2013).

Teshuva, Jacob, and Wolfgang Volz. Christo & Jeanne-Claude. Original ed. Köln: Benedikt Taschen, 1995.

Appendix

Fig. 1

From www.christoandjeanneclaude.net (grey line is time spent on preparation, tan tip is work actualized)

Fig. 2

From www.christoandjeanneclaude.net

Fig. 3

From www.christoandjeanneclaude.net

Fig. 4

From www.robertsmithson.com

Fig. 5

From www.christoandjeanneclaude.net

Fig. 6

From www.christoandjeanneclaude.net

Fig. 7

From www.bethel.edu

Fig. 8

From tate.org