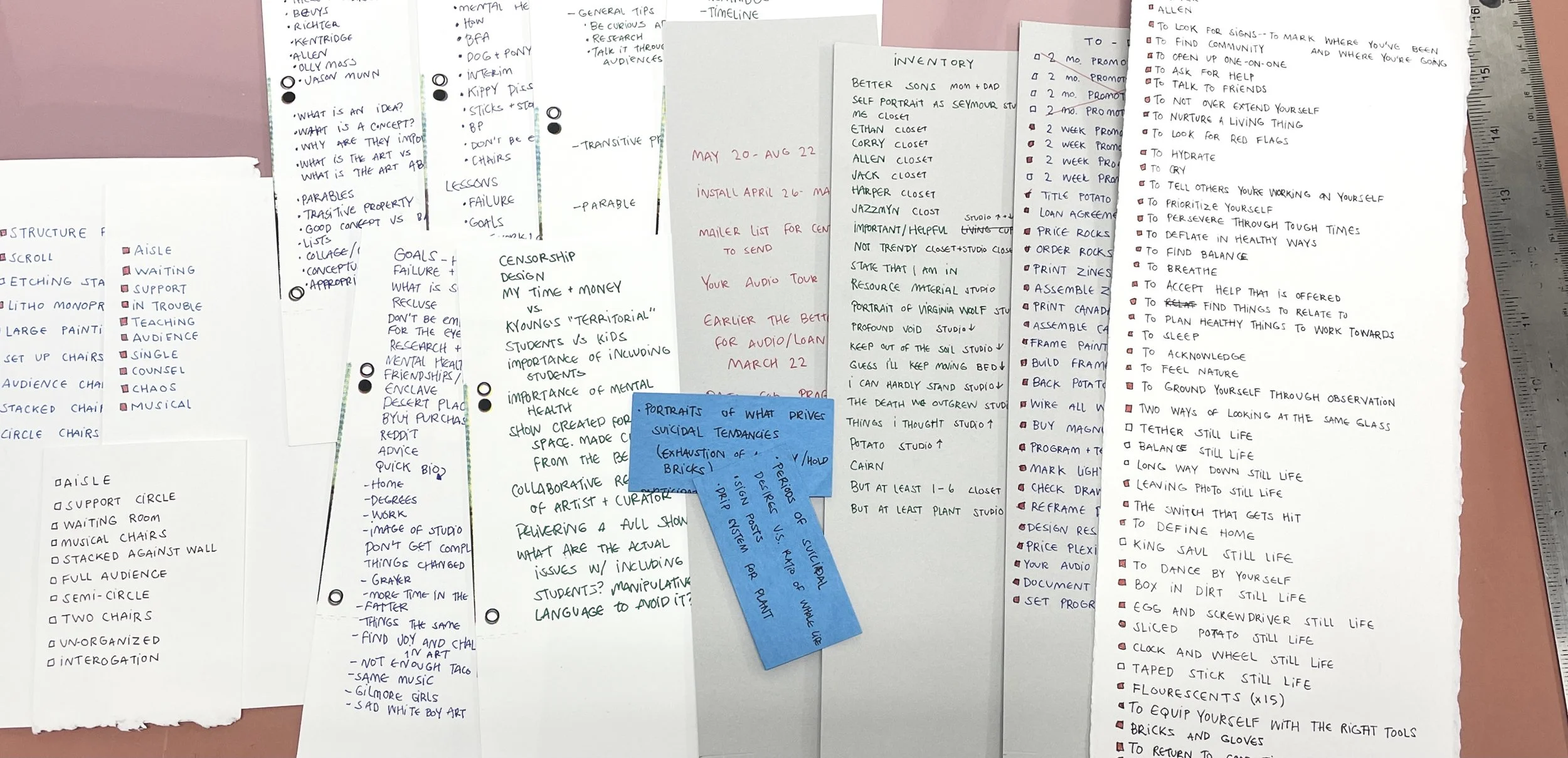

Lists are a key component of my art practice and I only recently became aware of this. Lists are an essential part of trying to keep a sense of control and overview of my life when things start to feel too chaotic and scattered in my brain. This function of chaos control was how lists first found their way into my practice many years ago, but since then lists have evolved in their role in my practice.

A list of lists:

To-do lists (completion mandatory)

To-do lists (permission to leave list incomplete)

Ideation lists

Inventory lists

Individual piece progress lists

Notes as lists

Art opportunities lists

Submission tasks lists

Exhibition packing lists

Exhibition planning lists

Exhibition artwork lists (hybrid inventory and to-do lists)

Presentation or artist talk brainstorm list

Presentation or artist talk outline list

Cv

The shape of my lists has become a good indicator of how a body of work or an exhibition is progressing. When I start making good, long lists I know my ideas are starting to come together and there is some synthesis taking place in my concepts. When those lists start to get rewritten and whittled down, I know I’m nearing the final set of works in the show for that particular time. It would benefit me to eventually analyze where lists reside in time in my practice, when certain lists are made, and what that may or may not represent about my work, i.e. ideation lists at the very beginning and the Cv as a running list of things in the past.

Many of the lists in my art practice are used as project management to-do lists. It took many years to come to terms with the fact that my to-do lists don’t all have to be checked off. This is a permission only granted to lists in my art practice (life to-do lists continue to have the requirement for completion). Permission to not complete an art to-do list only came from realizing that the idea still existed regardless of if I made it at that time.

Because of this, I don’t discard my lists.

And through the recent realization of the importance of lists in my practice, I am starting to view the process as something more akin to sketching. These lists are the closest thing I have to a consistent sketchbook practice currently. (I want to one day unpack the pressure I feel to keep a traditional sketch practice.) They are a form of sketching concepts through language rather than image. And like any consistent sketching practice, some entries take a more final form than others. Some entries are revisited later and reworked. And some entries are completely abandoned, only to live in their original list/sketch form.